A friend on Instagram asked me about a recent read, “Does it have an actual PLOT?” she said, “This year, I only want to read properly narrative novels with a beginning, a middle, and an end, not just beautifully-written descriptions of stuff that happens.”

An interesting comment. After all, isn’t ‘stuff that happens’ a plot? Not necessarily. One bit of ‘stuff’ has to be connected to the next, or provide a hook of some kind to keep the reader turning the pages. You would think this is a sine qua non of a novel, and I’m now rueing my reply to M. that I have recently been reading more detective fiction in search of plot satisfaction, as if crime and thrillers are the only place where we find such a thing, when in fact any decent novel will do the trick. After all, when pitching to agents, writers have to provide a synopsis of THE PLOT that demonstrates cause and effect, the what-happens-next, the crisis, the jeopardy!

So why do some perfectly respectable novels fail to live up to this expectation? In some quarters it’s accepted that a ‘literary’ novel is less plot-focussed, and this is sometimes true. Of my recent reads I give you Northwoods, a novel (and Pulitzer finalist!) that takes a particular place and unveils its inhabitants over time, leaving the reader to make the connections. A classic example of literary and semi-experimental fiction.

Novels like this (or plays – I learned this as a student of Sophocles!) can be described as ‘episodic’ – a collection of more loosely connected events (stuff) rather than a unified narrative. Reviews of Northwoods range from “a polyphonic marvel” to simply “disjointed”. Stuff happens, but there’s no single compelling thread. I enjoy books like this too, but I still need to feel there is an end point coming up, something that makes sense of it all. I almost laid Northwoods aside but it had enough to keep me engaged. It did satisfy, but it was an interesting journey rather than a race to see what would happen. I suppose a book which is agreed to have challenged the novel form may well frustrate someone in search of a more conventional example. However, while I do understand the need for a page-turner, I occasionally I feel I’ve turned the pages too quickly, and the faster I’ve read (or devoured?) a book, the less of it I’ll retain in the longer term. The way the story is told has to hold me as well as the story itself.

I’ve looked at my booklist for 2025 to see how many of my favourites stand up to the page-turning test. Leaving out crime and thrillers (which live and die by the plot) and also Robert Harris (Precipice and Conclave both offer jeopardy aplenty and need no recommendation from me), some of my favourites probably leave something to be desired in respect of a compelling plot even if I loved them for other reasons (Andrew O’Hagan’s Caledonian Road– epic! Michael Pedersen’s Muckle Flugga – astonishing!)

But here are a few which I would put in the literary category and which more than deliver in terms of momentum.

In no particular order:

Broken Horses by Kate Beales

A governess with a startling backstory arrives on a ranch in politically charged Patagonia. Think an exotic Jane Eyre, historical but with a contemporary feel. I ‘devoured’ it (but not too quickly!)

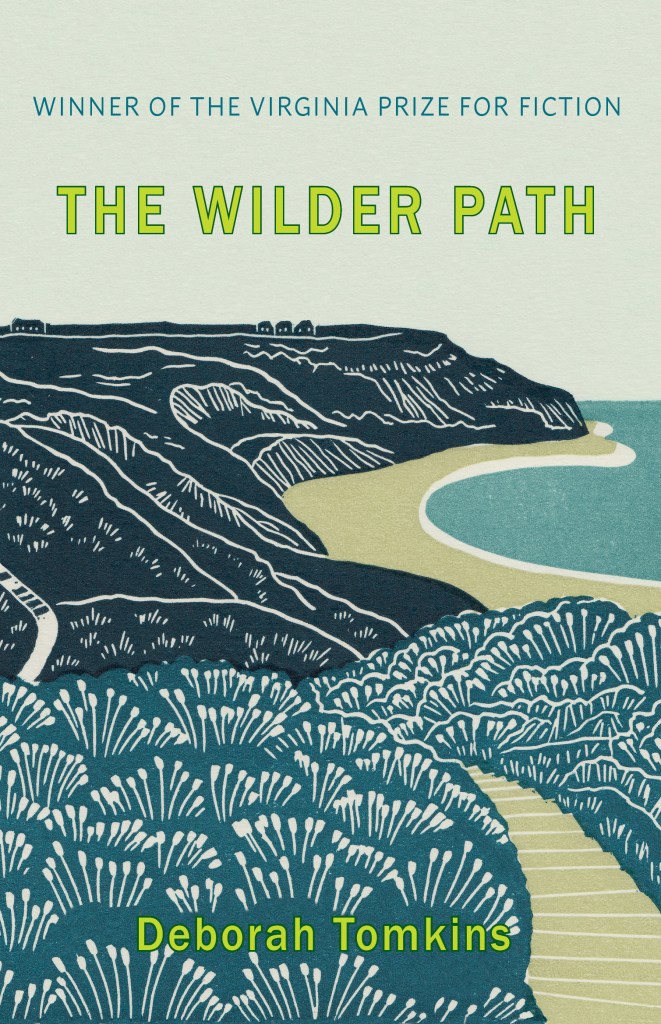

The Wilder Path by Deborah Tomkins

In a sudden winter storm an older woman is trapped in a cave. Much of the novel looks back to previous tragic events, but the tension is unrelenting.

The Betrayal of Thomas True by A.J. West

A galvanising adventure set in 18th century London and its molly houses, with an excellent twist.

And what of my own offerings?

I remember once opining that every novel should have a) a mystery and b) a love story. I think this was a simplistic way of recognising the need for the tension of a puzzle to be solved (plot) and emotional investment in the characters. I think A Kettle of Fish (still on Kindle or contact me for a copy) delivers on both of these and is arguably the most ‘commercial’ of my novels, not to mention quite fun to read!

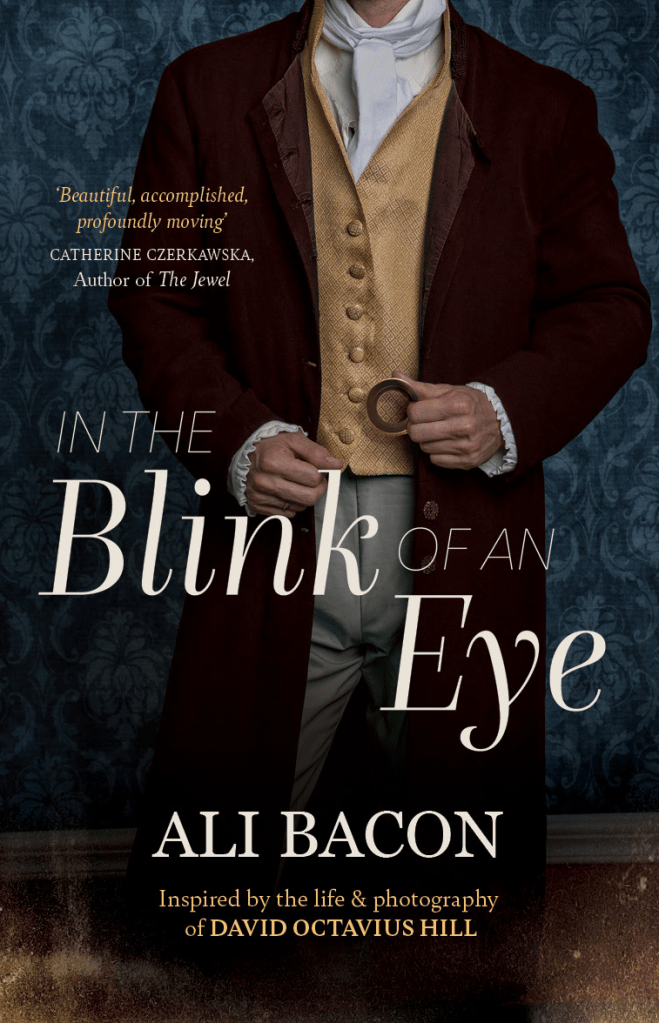

Writing In the Blink of an Eye was a joy, but I was conscious of creating a ‘jig-saw’ novel, one that would fall into shape piece by piece. If you’re in it for ‘the journey’, this one is for you!

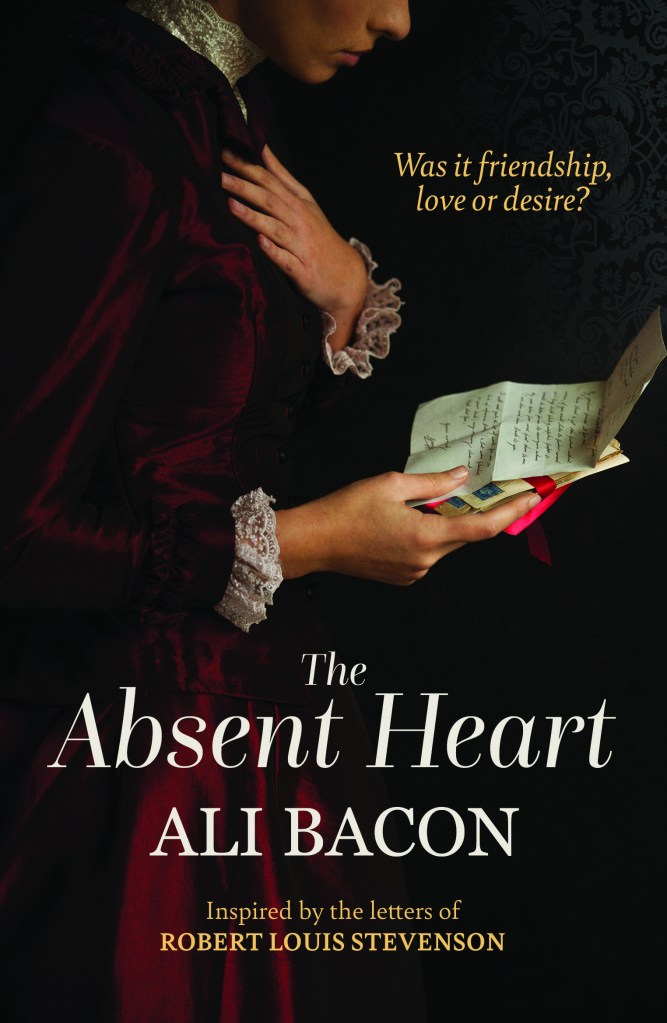

With The Absent Heart my approach in conveying historical events was more straightforward. I wrote not to create a page-turner exactly but very much with the intention of moving things along. And with a quantity of letters to deal with I even used one as a MacGuffin – the purveyor of a mystery or puzzle. I’m glad to say this paid off, with many readers claiming it kept them up reading late at night. So here’s my final suggestion for those of you who don’t want to hang around waiting for stuff to happen!