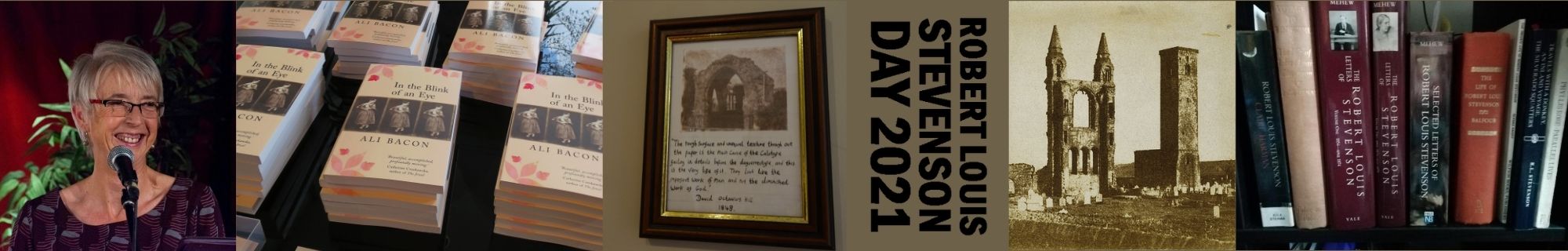

Going to the first ever St Andrews Photography Festival was such a thrill, only part of which was having my first ever one woman show. I’m happy to say the show was everything I wanted it to be with an attentive and appreciative audience. But in a way the real thrill was discovering I wasn’t the only one obsessed with the lives of a small group of people (all of whom died over 100 years ago) and their photographs. Which of course I knew to be the case. But it was quite something for my obsession to be making me part of something and to discover a shared obsession could manifest itself in so many amazing ways.

On my first day, on a rain-soaked photo tour led by Rachel Nordstrom (head of University Photographic Collections, organiser of everything and everybody) I met a collector and producer of stereoscopic photographs who in a gap between showers whipped out an i-pad and treated us to some of his creations. At the evening talk by world authority Dr Sara Stevenson (mentioned here) I was approached by someone trying to uncover the whole of D. O. Hill’s early (pre-calotyping) life. Then at dinner, (gulp – I was slightly star-struck to be in the company of several early photography luminaries) I sat opposite Rob Douglas who creates his own modern-day calotypes according to John Adamson‘s original instructions. Finally, at my own event on Friday evening there were people who had come to the same point from completely different angles: a lady who was interested in Hill and Adamson because of photographs taken by her great grandfather, and a descendant of one of the ministers who sat for D.O. Hill’s Disruption painting.

What all of us came to find was the sudden the ability to air or unpick details of St Andrews in the 1840s without having to explain or defend our interest. And we could learn from each other far more effectively than consulting a library or internet site. Rob Douglas – whose hands-on workshop I had missed – had already shone a new light on just what a painstaking business it is to produce a single calotype negative and Sara Stevenson made a sincere plea for anyone to contribute any materials or knowledge they might have stored away in a dark corner. And of course there were those special moments when a complete stranger echoes your own long-held thoughts – like the audience member who saw the image on my programme and sighed deeply, ‘Oh, poor Chattie!’ As if Hill’s daughter were a family friend. Because, of course, to us that’s what she is.

In the word ‘obsession’ there’s a hint of the pejorative, and I guess the adjective most commonly used of it would be ‘unhealthy’. You can certainly recognise an obsessive by a certain gleam in the eye and a tendency to catch you by the sleeve if you try to walk away. Yes, they can become boring. But I think we are mostly harmless and although some obsessions might have a touch of the dark side, most of them are good for us. They give us a a reason to learn and to connect with fellow obsessives. They lead us to places and experiences that help us grow. I have a friend who’s into Lord Nelson and another hell-bent on discovering all there is to know about Lady Ottoline Morrell. Why? Well why not? Although I’ve tried to unpick the origins of my obsession, it doesn’t really matter where it came from. These interests give us, if not a reason to go on, something to fall back on at least. Maybe this is what they call a hinterland.

Since coming home from St Andrews I’ve been to see the Painting with Light exhibition at Tate Britain where the Disruption Painting has been on show. The commission for this painting was Hill’s original motivation for trying out the use of calotypes and the beginning of his partnership with Robert Adamson, but having begun it in 1843 he didn’t complete it until 1866, close to the end of his life. I thought this journey might be a kind of final leg or even post-script to my research in to Hill and Adamson, but of course it might just be a new chapter.

The picture raised so many questions for me, not least the troubling issue of the colour of D. O. Hill’s hair which I’d previously mentioned to John Fowler, author of Mr Hill’s Big Picture, in which Hill is described as having ‘flowing blond locks’. Really? From the calotypes you would say that Hill is dark-haired, and in this Thomas Rodger portrait of 1855, possibly grey. In London I got as close to the picture as I possibly could to make my own assessment and I now I’m not sure. Brown with blond streaks I would say. Or has something been painted over?

Oh dear I am boring you now, but these things matter to obsessives like us. Mr Hill’s hair is definitely something to discuss next year in St Andrews.

Ha, seems you had a fab time. Long live those obsessions!

LikeLike