Adapted from my my Beyond the Book newsletter of September 2024. Sign up for future issues here.

If Frances Sitwell is my heroine, who is the hero? It would be easy to argue for Louis Stevenson (who has a way of taking centre stage even when he isn’t present!) but chief contender for male lead must surely be the third member of that curious love triangle, Sidney Colvin, Frances’s ‘companion’ for most of her life, also R.L.S.’s friend and literary mentor.

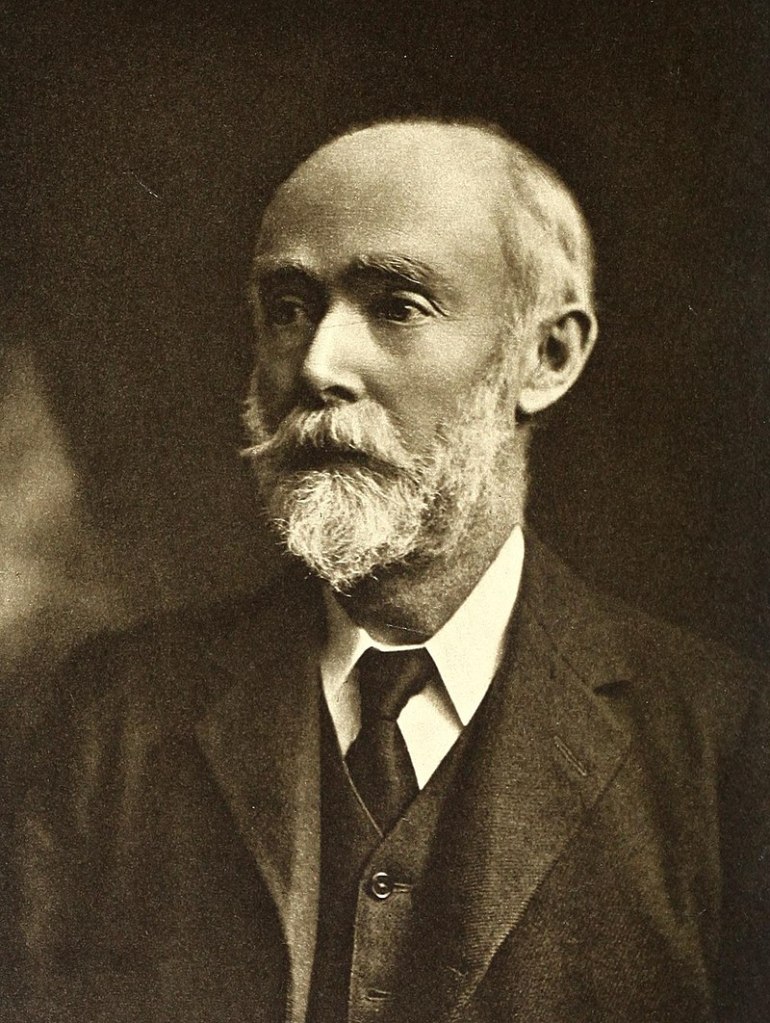

Only Stevenson fans are likely to have heard of Sidney Colvin, so who was he? The son of a ‘good’ Suffolk family who had fallen on hard times, from childhood onwards he had all the right connections, including a family friendship with the Ruskins. A graduate of Trinity College Cambridge, he also grew close to the William Morris and Burne-Jones artistic circle. He had an illustrious career as a museum curator (Director of the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge and later Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum) and authored a number of books, including one on Keats. According to his biographer[i], “art was his bread and butter, literature his love.” Surely all of this made him quite a catch for any intelligent well-read woman like Frances Sitwell when she needed a friend and supporter?

However, the image we are constantly presented with is of a man who is not innately loveable; punctilious rather than impulsive, stuffy rather than fun, and compared to R.L.S., distinctly buttoned up. In early drafts of the novel (where Sidney Colvin had an even bigger role!) I think I was too ready to accept this stereotype. Or as one early reader put it – what on earth did she see in Colvin?

Of course, it didn’t help the real Colvin’s case that distance (geographical and emotional) grew between the men when R.L.S. left for Samoa and Louis began to voice doubts over his old friend, as in this comment to Henry James, “he has a husk; inside it is good meat, but the husk is by most teeth invincible”[ii]. Then after Louis’s death, there was Colvin’s dramatic falling out with the Stevenson family over the writing of Louis’s biography, which made it easy for him to be cast as a villain.

But don’t forget that wide circle of friends Sidney Colvin was forever visiting, and if a letter from Louis to W.H. Henley from 1882 is anything to go by[iii], their friendship had plenty of boyish fun as well as literary endeavour. In later life, Sidney Colvin had his own literary salon, maybe not quite as glamorous as those hosted by Edmund Gosse, but still popular. Elgar dedicated his cello concerto to the Colvins and Henry James seems to have used him for a minor character in The Golden Bowl[iv], surely a mark of affection. And so I think Sidney Colvin’s presence was widely welcomed; he was liked as well as respected. What else can we deduce about him?

Surely it’s significant that in his own account of his life, (Memories and Notes of Persons and Places, E. Arnold, 1921) and in the later biography by Lucas, pride of place is given to other people. This could be a case of whole-scale name-dropping, or maybe it’s actually self-effacement, the idea that his achievements (and they were considerable) were less noteworthy than those of more famous or talented contemporaries. Glenda Norquay[v] sees in him a ‘willingness to be devoted’ (first to Ruskin, then R.L.S.) and ‘vibrating to the intensity’ of such presences.

So a follower rather than a leader, a willing devotee – whose lasting devotion was to his wife. Of one thing there can be no doubt. Sidney Colvin adored his wife and wrote several effusive descriptions of her. Lady Colvin, as she became, always called him Felix, suggesting a strong mutual affection. A contact in Australia recently alerted me to a reference in a Henry James letter to ‘Colvin and Colvina’, so a successful partnership, with her influence more than acknowledged by such friendly teasing. Perhaps it was through her influence that he made up with Louis’s biographer in the end, and in later years maintained ‘a cordial correspondence’ with Louis’ step-grandson Austin Strong, writing to him and his wife as ‘my dearest children.’[vi] From this it’s clear that friendship between the two families was restored.

For anyone who would like a broader picture of Sidney Colvin, there are plenty of decent online articles. As for photographs, a slightly more approachable version is housed in the V&A collection. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O103378/sidney-colvin-photograph-hollyer-frederick/

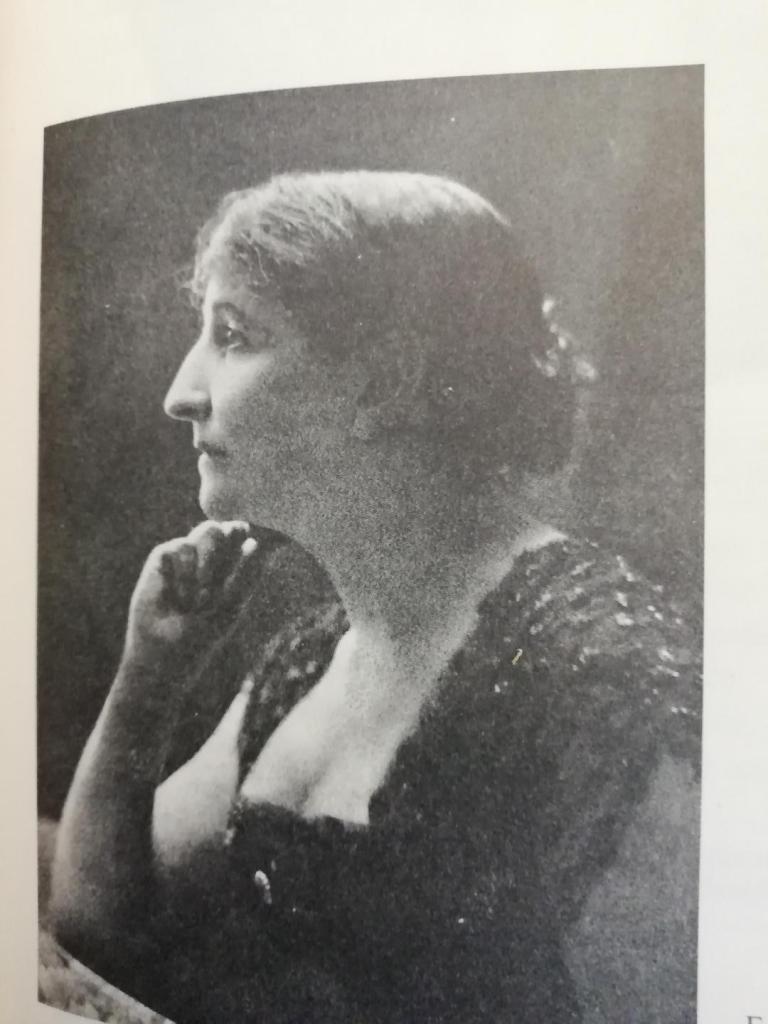

So far we have had an elusive heroine and an unlikely hero. Next time we’ll get to know Stevenson’s wife, Fanny, someone who could never be ignored!

[i] Lucas,E.V. (1928) The Colvins and their Friends, London, Methuen

[ii]Booth, B.A. & E.Mehew (eds.) (1994-5). The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. New Haven/London:Yale University Press. Vol.6, p.403

[iii] ‘theAffable Archangel’ Louis says, referring to Colvin, ‘has quite surprised me by his rowdy conduct’ Mehew, Ernest, ed. Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, Newhaven/London, Yale University Press, 1997

[iv] Tintner,Adeline R. (1974) “Sir Sidney Colvin in The Golden Bowl: Mr. Crichton Identified,” Colby Quarterly: Vol. 10: Iss. 7, Article 5.

[v]Norquay,Glenda (2020) Robert Louis Stevenson, Literary Networks and Transatlantic Publishing in the1890s, London etc., Anthem Press

[vi] Mackay, Margaret (1968) The Violent Friend, [abridged edition], London, Dent & sons